#Risks and Anti-Honey: Does Fashion Still Understand What Women Want?

Fantasy and function are not enemies. They are a pair, like inhaling and exhaling. Fantasy makes fashion desirable; function makes it possible. Everyone in the upper echelons of the industry knows this, but in the frenzy of quarterly reports, that knowledge is easily lost. Brands are under pressure: the market is cooling, spending is being reconsidered, and investors demand momentum. Hence—the reliance on the gesture. On the noise. On the "look at me now." But the gesture has a side effect: it ages quickly. A dress created purely for a visual image will tire of living in reality by tomorrow. At fittings, you have to convince it to sit well, not to work. And then comes a silence that the accounting departments can hear.Women today don't need "normal" clothes—they need smart ones. Quiet, but not boring. With character, but without caprice. The simple list of what is being read in showrooms and comments sounds almost utilitarian, and therein lies its strength. Pockets where the palm won't get stuck. A waistband that doesn't migrate on the first step. A bag strap that doesn't slip off a wool coat's shoulder. Lining that glides instead of electrifying. Shoes that can handle tile and asphalt—all in one day, without changing pairs. A dress that looks beautiful in motion, not just in a static, frontal shot. Fabrics that hold shape without being heavy. Colors that match the skin instead of clashing. These sound like "details," but respect is built from details.I would add another point here—authorship. Whoever is behind the garment is responsible for the gaze. When there are almost no women at the top of creative departments, it’s no surprise that the female body becomes a field for thought rather than an address for care. Authorship changes the angle of view: instead of "how to show it," the question becomes "how will this live?" This does not cancel daring; it adjusts the goal. And the language immediately aligns. It’s not "here is an image for you," but "here is your rhythm." For example: a suit with a soft shoulder line and a well-considered armhole solves half the day’s questions. A skirt with an inner corset-waistband provides a fit that doesn't need constant adjustment. A coat with the correctly calculated weight in the hem calms the gait. Nothing overly complex; just competent mechanics and honest time dedicated to development.Next—marketing. We love beautiful stories. But a story not grounded in experience quickly smells of emptiness. It is time for the industry to stop explaining to women that they "misunderstood" the concept and start asking, "How did this fit? Where does it pinch? Where do you wish for air?" The answers are not found in creative briefs, but in returns. The "reason for return" field holds the most useful texts of the season: small armholes, coarse side seams, unpredictable length, lack of a bust fastener, too narrow a zipper on a boot. We often read complex manifestos for collections and rarely read simple fit reports. Meanwhile, future brand loyalty is born the moment the zipper closes without a struggle.Clients vote in two ways—with money and with attention. Money votes for practicality without boredom. Attention votes for an authentic voice without violence against the body. This season, items sold well where it was clear that time was spent not on effect, but on technology: correct trouser fit (yes, again), a jacket style that accommodates different bust sizes, a bag that doesn't press against the collarbone. This doesn't mean "basic for everyone." It means "respect for everyone." You can create outrageous cuts, but they must be wearable, or they are just noise.What should houses do right now, briefly and concisely? Restore technical discipline to the process. Add more time for fittings, material testing, and controlling the weight of hardware. Update sizing charts—not on paper, but on real bodies. Restructure communication: less "top-down" discourse, more service-oriented explanations of "why this is constructed this way." Support female authorship—not just on the runway, but in product teams, workshops, and merchandising. And finally—re-examine the usual KPIs. A garment's success is not just reach and reposts. It is the return rate, the wear life, repeat purchases, and reviews that say, "I bought it in another color." These data points are boring for a press release, but they heal the brand.The scene with the mouth braces will be remembered. It is already a meme, an ironic image, a subject of debate. But its main benefit is not the noise, but the reminder: fashion does not have the right to speak for the woman. Fashion must give her voice and form. "Form" is not just the silhouette. It is the way the garment exists in a real day. When a dress withstands the subway, the office, the restaurant, and the playground—without losing dignity—that is when we are back on the same side.The paradox of today's fashion is that it can do everything: any material, any technology, any supply chain. What is missing is the simplest thing—to reconcile the dream with the body. Not to diminish, but to reconcile. Simply put: fantasy is responsible for the desire to take the item into the fitting room. Function is responsible for the desire to leave the house wearing it and return to it tomorrow. If the latter part is ignored, only beautiful shots remain. And we already have an excess of beautiful shots. What is missing are clothes that are returned to.Another important line is age and diversity. Women at 20, 35, 52, and 68 might shop at the same house, but they are rarely offered different depths of design. Correct lengths, alternative fits, transparent fabric explanations ("doesn't attract dust," "is not afraid of rain," "holds at the elbow") are needed. We need to stop being ashamed of simplicity. In our time, simplicity is service, not compromise. The woman's voice is heard where the clothing does not force her to apologize for her choice.

Yes, the industry operates in a competitive field. Yes, everyone wants speaking images. But speaking images have one flaw: they talk to themselves. The woman, however, talks to reality. And if the garment can do that for her—softly, reliably, beautifully—it will be purchased and repeated. This is the "luxury of the future": not a scream, but precision. Not a performance for the sake of noise, but a construction for the sake of life. Not "we know what you need," but "we listened, we accounted for it." Therefore, the answer to the question, "Does fashion still understand what women want?" is this: it understands exactly as much as it is willing to be silent and check everything with its own hands. To spend an hour with the pattern-maker instead of five minutes on the stage. To give the final word not to the press release, but to the fitting room. Women don't need permission to have a voice—they need respect for their time, their spine, their routes, and their roles. When that is present, fantasy gains its rights. It starts working again as a force, not as decoration. We love fashion for precisely this—for its ability to turn the day into a better version, without exacting a toll from the body. And we will continue to talk about this, because this is our side: the closest to life. If the industry returns to the habit of listening, the debate will disappear by itself. What will remain is what it was all started for: a garment one wants to live with. Full stop.

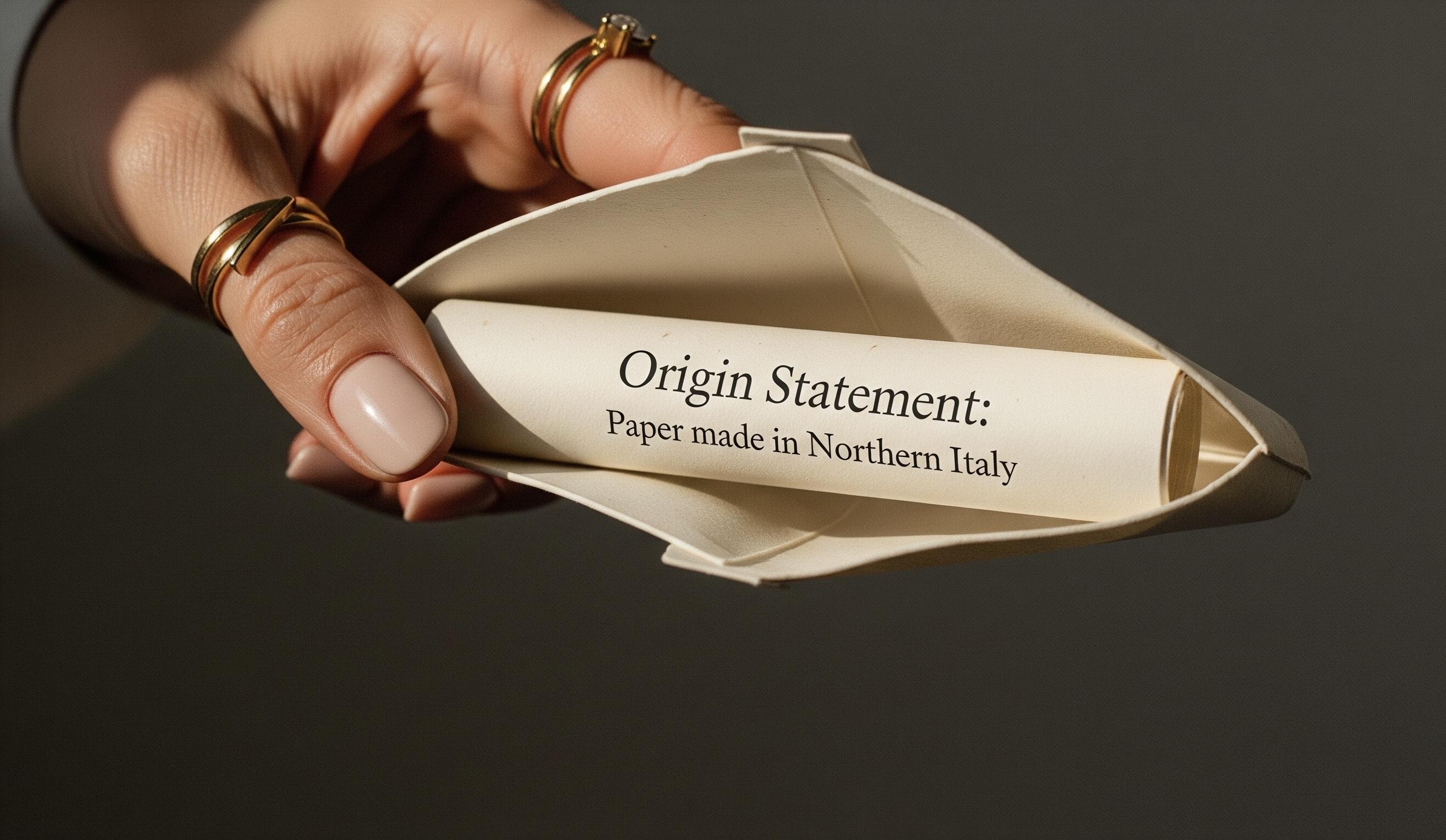

Milan shines, machines hum: "Made in Italy" in the spotlight.

Milan Fashion Week kicked off to a new buzz: camera flashes, a trailer-film from Demna for Gucci, and talk of "new minimalism." But beneath this soundtrack, another bassline rumbles: supply chain scandals. The glossy store windows are like a screen, and behind it lies craftsmanship, contracts, subcontracts, night shifts, and the incessant hum of sewing machines. The key question of the season is this: who pays the real price for that perfect stitch? The legal term that PR directors now know is "external management." In 2024, a Milan court placed Giorgio Armani's Italian subsidiary under the control of external administrators following an investigation into labor exploitation by its subcontractors. The factories, run by intermediaries, were found to be using migrants and violating regulations on working hours and safety. The brand stated it has zero tolerance for violations and would tighten controls, but the measure itself sends a signal to the market: "I didn't know" no longer works as an alibi. Dior was hit by a similar blow in late 2024. Prosecutors described a sprawling network of Chinese workshops in Lombardy: multi-layered subcontracting, rock-bottom prices and deadlines, resulting in luxury goods made with labor violations. The court again chose the path of external management for the brand's Italian structure—a harsh, public, and educational move.The summer of 2025 added another name: Loro Piana. The order was the same: an inspection of contractor conditions, and the swift appointment of external administrators while the company cleans up its supply chain and implements strict controls. The business language is dry, but the meaning is emotional: "Made in Italy" is no longer a default certificate of trust; it's a contract that the industry must prove every day.How does this shadow choreography work? A fashion house signs a contract with a reputable manufacturer. To meet deadlines and margins, that manufacturer divides the order and sends it "down the ladder" to where it's cheaper, faster, and closer. And then further down. At the third or fourth level, workshops with "flexible" schedules and under-the-table wages appear. This is where stories of people living directly in the factory, working night shifts, and getting fined for being slow are born—all the things we're used to reading about in distant countries, not Tuscany and Lombardy. This geography was also illustrated by cases in 2023–2024, when Italian police and prosecutors documented a network of Chinese workshops working on luxury contracts. The paradox of Milan is that it's still home to a full-cycle production of clothing and footwear in Europe—weavers, tanneries, last-makers, assemblers, finishers. The sector's volume is over one hundred billion euros a year, according to industry associations. This isn't a museum of crafts; it's a real economy with an army of family-owned factories and hundreds of thousands of jobs. When leaders of major groups call to "save Italy," they're not talking about nostalgia but about industrial infrastructure, without which Europe loses its expertise. Why did this issue surface now, against the backdrop of Gucci's high-profile reboot? Because two storylines have intersected: brands are desperate for growth after a cooling in demand, and the state is simultaneously tightening control. The judicial tool of "commissariat" works quickly and demonstrably: appointed administrators enter offices, review contracts, re-sign quality and compliance rules, and shut down risky operations. It's painful and expensive, but this "public scar" forces neighbors on Via Montenaponeone to re-examine their own chains. And what are the fashion houses themselves doing? Some are restructuring contracts: fewer links, longer deadlines, and a higher per-unit rate for the workshop. Others are bringing key stages "in-house": leather goods next to the archive, heels next to the atelier. They're implementing traceability—from a roll of leather to a box in a boutique—and changing audits from a "once-a-year visit" to a "constant presence." Auditors now live on the lines instead of just dropping by for coffee. Even the audit systems themselves are being rewritten after criticism in 2024: previous checklists often skimmed the surface and didn't capture the real temperature of the workshop. There's a lot of morality in this conversation and even more . Luxury relies on trust: we buy the promise of quality, time, and the human hand. When that hand in the news turns out to be tired and underpaid, it's not just the brand's image that's destroyed—it hits the margins. Supplier scandals affect market capitalization more than a debate over whether a collection is "liked or disliked" because they undermine the foundation: the brand's right to a price premium. And yet, this story has a chance to end with maturity. On the runways, the word "honesty" is currently adored: quiet silhouettes, natural textures, and conscious codes. True honesty begins with the people who sew this "quiet" luxury. The market is already accepting a new math: fewer iterations, more transparency, and simple shapes not for the sake of savings but for a production rhythm that the human body can endure. The paradox is this: Italy is a country where this can be done correctly. Craftsmanship and control coexist here: municipal inspections, strong unions, courts that move quickly, and a network of small workshops ready to work as quality labs. This ecosystem needs to be protected—not with slogans about "legendary artifacts," but with the boring, expensive organization of labor.How will this echo in the coming seasons? First, we will see a "slow-down of luxury": fewer items in capsules, longer pre-production, and more re-releases from the archives instead of the exhausting race for newness. Second, the runway will give craft a name: a closed-toe shoe with a hand-braided detail, a heel with micro-engraving, and an inner seam that will be a source of pride just like a logo. Third, brands will begin to speak honestly about the price: not just "for the leather and design," but "for the workshop where the lights are turned on at six in the morning but are turned off on time." And yes, backstage in Milan, they are still arguing: "Can the new Gucci replace porcelain with steel, and a show with construction?" But the louder we talk about fashion, the more confidently the chorus from the workshops sounds: "Make us part of the story, not the shadowy credits." Because the formula for luxury in 2025 is this: without dignified labor, there is no beautiful product. Everything else is just a new film and a new lookbook. What's important to remember from the facts: a Milan court introduced external management in the Italian structures of Armani (2024) and Dior (2024) due to violations by subcontractors; in 2025, the same measure affected Loro Piana. Inspections documented a network of Chinese workshops at the deeper levels of contracting in Lombardy and Tuscany. Italian fashion is Europe's largest production base and one of the pillars of the country's economy, which is why the scandals here are louder and the consequences are more noticeable. In short, Milan is dictating the season once again. Only this time, the real trend isn't a silhouette—it's production ethics, and it will become the most wearable code of the year.

Air isn't a phone. It's a subtle excuse to always have a piece of jewelry in your hand.

And there's the economics of it. The most expensive currency is attention. The Air is careful with it: it doesn't demand endless micro-management, doesn't invite itself into every photo, doesn't make you fuss with extra millimeters in your pockets. When a thing conserves my resources, it becomes part of my personal system of "luxury through comfort." In this sense, the Air is closer to a good cut than to "hardware": it liberates, it doesn't weigh you down. And yet—where's the drama? In the details. In how the titanium catches the first ray when you get out of a taxi. In how the phone disappears under a lapel, making your posture straighter. In how friends in the front row stop tapping and start talking. When an accessory makes people look at each other, not into themselves—that's magic. And that's exactly what the new luxury wanted. The finale is like a final walk down the runway: short, precise, not drawn out. The Air is a subtle gesture of high taste. A phone that behaves like the jewelry of the day, without pretense and without a scream. An object that respects the wardrobe and its owner. And yes, buying such a thing isn't about megapixels; it's about character. We live in a world where any "icon" can grow tired of its own importance. The cure is simple: return to the line, return to tactility, return to manners. The Air does exactly that.

The rest is up to us. To wear it wisely. To take it out at the right time. And to add to the titanium something no corporation can: our own voice.

#aesthetics of observation

Color coup: when Hermès dictates the iPhone palette

When this iPhone appears, it will be the first phone that does not need to be explained. It will not be called a color. It will be called a name. This is — Hermès. Even if officially it will be named Orange Glacé or Sunset Ochre. In speech, it will become a name of its own order. And the people who choose it will choose not a device. They will choose a gesture. They will choose to be inside a line that began long before them — in a workshop that smells of wax and leather, and where light does not ask permission to enter.

In the very center of the industry, where form costs more than function and silence is a luxury, Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy has found itself trapped in the glare of its own shine. While the flagships’ windows continue to reflect the light above Avenue Montaigne, heat is building in the depths of the corporate body. Leaks of internal information, ethical imbalance, declining sales, and a tremor in trust have all fused into a single term, quietly, almost lexically: luxury malaise — an ailment for which recovery cannot be purchased, only the acknowledgment that the system needs shade. Not retouching, not injections, not performative growth, but a pause. Against the backdrop of the second quarter of 2025, when the market expected signs of strength from LVMH, reports seeped into the press: group sales fell by 4%, profit by 15%, and the key fashion and leather goods segment suffered most — down 9%. On its own, a moderately worrying signal, considering post-pandemic volatility and a slowdown in Chinese consumption. But the issue wasn’t the numbers, it was the backdrop. The media noise surrounding the release of results was not just loud — it was narratively awkward. Headlines no longer delivered the usual confidence. Where “growth” normally appears, there was now “fatigue.” And even HSBC, in an attempt to soothe the market, framed its main thought like this: “It’s rough… but won’t get rougher.” For the titans of luxury, already a defeat. Yet perhaps the most important part of this situation is not the drop in figures, but the drop in illusion. The very structure of the group — its advertising tempo, its algorithmically accelerated production of meanings, product collaborations, and ambassadors — has reached a phase where external gloss collides with internal overload. And here appears the first crack: leaks. How data within LVMH ended up in the hands of journalists remains a question that the press office has carefully skirted. But the fact remains that contract schemes, supply chain locations, contractor names, and procurement policy details have escaped. This became possible not because of technical vulnerability, but because of the architectural pressure of the system itself: too many players, too many entry points, and — too much speed. And suddenly it is not Dior dictating the tempo, but a Telegram channel. Not Givenchy creating intrigue, but a PDF document sent by an anonymous source the night before the quarterly report’s release. The second layer of the story concerns labor ethics. According to an investigation published alongside the report, outsourcing structures were found in the supply chains of several of the group’s brands that practice questionable working conditions in South Asia, some with accusations of excessive overtime, unsanitary conditions, and violations of minimal social standards. And although LVMH quickly issued a statement about “isolated incidents” and “work to improve practices,” these words no longer carry their former crisis-management power. Today’s consumer — especially in the premium segment — tends to associate themselves not only with the aesthetics but with the ethics of a brand. To fall in this aspect is like overturning a mirror. The third crack is visual and commercial fatigue. The gloss no longer warms — it blinds. When each season carries five to ten creative launches, when a single brand simultaneously presents capsules, NFTs, celebrity installations, and a new fragrance line, even the loyal customer begins to lose focus. Abundance ceases to be a gift. It becomes noise. And luxury, historically built on the economy of scarcity, loses its strategic silence. This moment is exactly what the term luxury malaise captures — literally “luxury malaise,” but pointing not to illness, rather to overheating. Overuse, overexposure, overpromising. When luxury loses the right to pause, it loses its value. And more and more often, instead of attraction comes the weary “Again?” at yet another launch. Why does LVMH need so many lines at once? Why a news item every week, a launch every month, a major report every quarter? Because the system does not allow for pause. Because the spotlight doesn’t know how to turn off. And yet this is precisely what becomes the signal for shade. Why does this matter right now? Because for the first time in many years, the very language of luxury has settled. Its aesthetic force is thinning. The marketing palette, honed over decades — from Matelassé to Monogram — is starting to feel mechanical. Phrases from press releases have become predictable. Even the visual solutions in campaigns seem to repeat themselves: staircases, silhouettes, twilight gazes, slowed walks, leather, light, drapery. Still beautiful, but now — without risk. Which is why the question that should be asked in this situation is: perhaps the brand truly needs shade? A place without a camera. Silence. The absence of a release. A retreat into deep work with materials, not images. Reinterpretation. Total reduction. Turning off the algorithm, even if it leads to a temporary loss of momentum. And in this sense, as paradoxical as it sounds, the current crisis could be a rare opportunity. An opportunity to return to essence. To remember that luxury is not KPIs and not stock prices, but the architecture of experience. It is texture, not volume. It is the silence after the show has ended but the feeling remains. Not a new collection, but a new quiet. Luxury has always lived in the pause, and when it is deprived of the pause, it ceases to be luxury. What is happening with LVMH is not catastrophe. It is a marker. A signal. The beginning of a new cycle, where the winner will not be the loudest but the most resilient. Not the fastest, but the most precise. In an era where the market is overheated and the language of luxury oversaturated, it may be that shade becomes the new light. Not as refusal, but as strategy. And while luxury malaise travels through the feeds of BoF, HSBC, WSJ, and Telegram channels, a new awareness is ripening within the industry: pause is not failure. Pause is potential. And perhaps the greatest luxury of the 21st century is the right to one’s own shade.

#Strategic Fragments

Vibe marketing: when a prompt becomes the new brief

The benefits are on the surface. Speed: creativity no longer gets stuck in endless briefs but is born at the rhythm of TikTok—iteration, version, release. Scale: one scene can be broken down for a dozen markets, each with different weather, different cameras, and different color preferences. Democracy: small teams get the power of large ones, leveled by their tools. Digital twins—digital models—free you from the logistics of photo shoots: the brand's face can "work" for 24 hours from a server studio, without getting tired or being late due to flights. But along with speed inevitably comes smoothness. Where the process is shortened, the small stitches that make up character disappear: the awkward laugh between takes, a glare that got into the shot unplanned, the strange fold of a jacket that makes the look feel alive. The algorithm selects "average beautiful"—and you can hear it. The visuals start to resemble impeccably retouched skin that, for some reason, is not memorable. In beauty, this is deadly: we sell a feeling, and a feeling loves a human imperfection. Therefore, "vibe" as a technology only stands when it has three pillars. The first is provenance. Every render, slogan, and shade must have a passport: from what sources the dataset was collected, whose faces were used as the basis for the training sample, and what rights the digital twin models have signed. Without a passport, the glow becomes fishy: it shines, but it smells of questions. The second is taste. You need an editor who has the courage to say "it's too perfect" and return the atmosphere to the shot. This is not a conservative, but a conductor of imperfection. He knows that real skin has pores, real cities have fog, and real stories have pauses. It is he who adds a hand gesture, a half-tone of a voice, and the "grime" of light that makes a campaign memorable to a polished image. The third is ethics. A digital twin without a clear contract is not technology, but a trap. We don't draw people from machine memory; we collaborate with them: payment, terms, usage control. The public loves miracles, but even more, it loves trust. And yes, a simple AI-assisted label saves everyone's nerves: honesty here works better than any contouring. What does this look like in practice? Imagine a lipstick launch. The brief: "a red without aggression, a lip silhouette that invites conversation, not a selfie." The first wave is done by the assistant: texture options, 20 lighting approaches, 40 timing grids for vertical videos. The taste editor steps in: removes the "cinematic" feel, asks for a matte glass tone, suggests replacing the fourth scene with a close-up of a breath after a phrase. Next—the studio: yes, a live one, with a makeup artist who argues with the cameraman about how the pigment "sits" on different phototypes. And the digital twin—for adaptations, for the content back office, where you need things quickly and in volume. The result: the speed of AI, the substance of the studio, the taste of a human. It is this triptych that gives a campaign a resilience that won't be washed away in the first week of sales.

Business loves numbers, so here's a quick "traffic light." Green: Transparent AI policy, agreed-upon digital faces, a clear registry of sources, live shoots where you can feel the skin; a taste department that has veto power. Yellow: "Same-as-everyone-else" shots with perfect geometry, endless renders instead of a day on set, a lack of names in the credits; a fear of labeling AI involvement. Red: Anonymous datasets, cultural appropriation without consent, "uniform beauty" in countries with diverse body types; digital twins created from thin air. A separate layer is language. AI is fantastically good at remixing clichés: "glow," "lifting," "velvety texture" will appear in ten variations in a minute. The task of the copywriter is to bring back the scent. The vocabulary of beauty has always been a poetic business: "morning tea on the balcony," "oxygen in the metro after rain," "the warm light of a pharmacy in December." These images are built from life, not from a model. The algorithm will help break them down into patterns, but the author creates the reason to breathe. Therefore, the best text in the AI era is written with a simple rule: first live the scene, then prompt. Another fear of the industry is, "what if we are replaced?" The answer is like a conversation about brushes and fingers: the tool comes and goes, the hand remains. AI levels the playing field for production, but it doesn't level the ability to hear the silence of a shot. Where brands turn the assistant into a partner, a new profession emerges—the vibe director: a person who composes not a plot, but a microclimate. He says: "Here—dandelion light," "Here—a pause for three heartbeats," "In this scene—a muffled 'sh' sound." The assistant has speed, the editor has taste, and the brand has responsibility. Only in this trio does "vibe" turn into capital.

And finally—about trust. Beauty has always sold a dream. Now the dream has become interactive: it can be prompted, scaled, and rendered overnight. But a dream without a physical body deflates. I look at a campaign and ask three questions. Do I feel skin, not just pixels? Do I hear a voice, not just a trend? Do I see people in the credits, not just the word "AI" in a footnote? When the answers are "yes," the wallet opens on its own, because I'm not buying a picture—I'm buying an experience from which my personal memory is then formed. Vibe marketing has arrived seriously and for the long haul. Let it remain a conductor's baton, not a cudgel for taste. We have already gained speed. Now it's time for resilience.

#fashion notes

essay 1. digital@dior: when couture steps beyond the mirror

#female gaze

how did you know, sotheby’s, that i was waiting for her?

i didn’t hear the hammer fall, but i felt the room at sotheby’s grow quieter—not the kind of quiet when everyone holds their breath, but the kind that remains when something real slips out of sight and passes into another dimension, into the place where it is no longer the object that speaks, but memory. jane birkin’s bag had been sold. not “one of,” but the one. the bag made for her in 1984, on a flight between paris and london, when she—young, bold, with hair gathered in a careless knot—complained to jean-louis dumas that her woven basket wasn’t spacious enough. she described her ideal bag: soft, leather, practical, feminine but without fuss. dumas sketched it on a napkin. the birkin was born out of fatigue, out of spontaneity, out of the need to simply be herself. the bag that went under the hammer for over eight million euros held not gold but traces. black box leather, the color of inky night—worn like a diary carried without a cover. brass hardware—dimmed like rings on fingers you haven’t taken off for years, not even in the shower. a strap that could not be removed. nail clippers tied to the handle—like a pendant, like a relic, like a sly mockery of everything called functionality. she used that bag for nine years. not like a glossy-magazine heroine, but like a woman whose hands were full—with a child, a notebook, a cigarette, a life. it wasn’t an accessory. it was a stage. the bag as theatre, as a letter without text, where every seam was a phrase, every scratch a memory. she carried it to the supermarket, to film sets, to protests. not carefully, not reverently. without display-case distance. because a real object lives. and lives with the body. when it was put up for auction, the lot description read: “the original birkin. 1985. black box leather. jb initials.” but what can you say about a woman who lived part of her life with an object, beyond initials? what can you write in a listing beyond weight and year, if at the bottom of that bag there were crumbs, letters, rouge, candy wrappers, coins, keys to apartments where she no longer lived? nine people fought for it. the bidding lasted ten minutes. then silence. the hammer. the final nod. the winner—a japanese collector. the question remains: what did he buy? leather? rarity? history? or the right to keep what a woman left behind—like a scent on a scarf, like a note on a wall? jane parted with that bag in 1994—at a charity auction to support an aids foundation. she let it go easily, as if it had never owed her anything. it wasn’t a rejection. it was moving forward. because women who know who they are don’t hold on to things. they let them go on living. after. without them. that’s what those who are sure of themselves do—even in scuffed shoes, even with hair undone. you don’t feel luxury when you look at photos of that birkin. you feel a body. a woman’s body. warm. unshowy. a body that lived in paris. slept with the window open. spoke in a mix of english and french. cried in the kitchen when no one saw. laughter. cold hands. a manicure. a bag full of life that needs no translation. now it’s gone. to tokyo, perhaps into storage. or into a private collection, behind glass. but as the hammer fell, i thought of my own bag. not a birkin. not worth millions. just the one i carried for six years. in it there’s still powder. a letter. a key that opens nothing. i don’t throw it away. i hold it the way you hold someone else’s letters—with care, with warmth, with gratitude. jane birkin’s letter isn’t in her autobiography. it’s in that bag. it’s unwritten. it’s lived. like the rhythm of a walk, like a voice, like a glance. and we, women, keep reading it. every time we take our own bag. every time we put our stories inside. every time we stuff it with everything—because we always carry a little more than it seems. i believe it wasn’t the brand that made the birkin. jane made it real. and when the brand wanted to replicate the form, it was already filled with meaning. because the true form is the one that holds the impression of a woman—not her style, her presence. the sotheby’s scene wasn’t about luxury. it was a moment of silence into which a woman entered—through an object, through a life, through what cannot be faked. because breath left on leather cannot be cloned. if you ask me if i want such a bag, i’ll say i already have one. not by name. by essence. it knows me. and that is enough.

la beauté vuitton: when makeup becomes a system of power

#strategic fragments

women@dior & unesco: couture with a mission

#Aesthetics of Observation

Prada — the gesture of tucking hair behind the ear: the chill of self-control associated with Prada’s heroines

#Brand Analysis

Celine and Phoebe Philo’s Minimalism: How Sharp Lines and Silent Chic Created a New Code of Feminine Power

“I Don’t Want to Be Beautiful, I Want to Be Interesting”: Miuccia Prada’s Philosophy and the New Aesthetics of Meaning

#Microcontent

Glasses as a veil of daring.

#fashion notes

Galliano — architect of dreams and Dior’s couture alchemist🖤

He was born in Gibraltar, in air that smelled of salt, port ropes, and a distant wind from Africa. From day one, his gaze didn't wander over toys but over the folds of his mother's dresses—he noticed how the fabric breathed with every step, how the light played on the hem, how the hem could betray joy or fear. From the age of three, he could watch for hours as his mother tied a scarf, as she rolled up her sleeves, and he saw in these movements not everyday life but drama. He didn't want to be a knight, like other boys—he wanted to be the one who sewed the king's cloak. When the family moved to South London, he found himself in a neighborhood with the smell of fried fish, gasoline, and rain on cobblestones. The dirty shop windows reflected his thin face with burning eyes, and John dreamed not of knightly swords but of mantles for heroines who saved not the world but their pride. He walked the streets as if in a play: puddles under his feet seemed like mirrors for imaginary shows. Even school corridors were catwalks for him—he imagined that one day women would walk down them in dresses he would sew, and their heels would beat in time with his inner music. At home, he built castles out of pillows and wrapped himself in curtains, imagining himself as a mannequin in a palace hall. A ball went on in his head every night, a new character was born every day. He memorized the color of the old carpet in the living room, the texture of the sofa covers, how the leather of the armchair cracked under his fingers—he absorbed everything like a sponge, and this became his language. In his teens, he was too strange for his peers: he wore his grandmother's scarves, sewed feathers and scraps of tulle to his school blazer, and dyed his hair in strange colors long before it became fashionable. His classmates teased him, but he wasn't angry—he imagined how one day they would be captivated by his shows. And in those moments, he felt not like an outcast but a harbinger of a great show. In the evenings, he locked himself in his room and drew silhouettes of women on old newspapers with waists narrower than a quill, with shoulders resembling palace cornices, with eyes full of cold fire. He didn't just invent clothes—he created heroines: divorced duchesses, midnight murderers with scarlet lips, witches in lace dresses that seemed to choose whom to curse. After entering Central Saint Martins, he found his flock—the air there smelled of wet ink, old mannequins, and hopes for a revolution. Every corridor of the institute was like a labyrinth where students didn't sleep at night and cut the world according to their own rules. John was a fanatic: he could go for weeks without going outside, experimenting with fabrics, burning holes in silk, dropping drops of paint on velvet to understand how they would soak in and dry. He carried scissors with him, like a pianist carries notes. His 1984 graduation collection, "Les Incroyables," was more than a graduate show: it was the resurrection of the terror of the Great French Revolution, but through the prism of punk and decadence. Models in cloaks, with torn jabots, with asymmetrical vests, walked the runway like characters from Jacques-Louis David's engravings, but with a crazy gleam in their eyes. The atmosphere was like in an underground theater: part grotesque, part brilliant revelation. This collection was bought right off the runway—no one could remember such a thing happening to a graduate. This is how the John Galliano brand was born, which immediately began to sew stories, not just things. In his first workshop, the walls were hung with prints of 18th-century paintings, newspaper clippings about bohemian scandals, and tiny paper dolls on which he experimented with draping. The atmosphere there was like an alchemical laboratory: everywhere were scraps of fabric, hooks, feathers, silk ribbons, the dye-stained hands of assistants, and John, flying between the tables with a cigarette, the smoke of which smelled of a mixture of vanilla and tobacco. Every morning he began by dousing himself with cold water to wake up in his madness, and then put on a suit that looked as if a mad marquis had sewn it: a floor-length cloak, a shirt with ruffles, a vest with gold buttons. He didn't just work—he lived as a character in his own show, not turning off the drama even outside the atelier door. In his notebooks, ideas for ballet tutus flashed, but not from tulle, like classic ballerinas, but from hard, shiny leather the color of hematite and inky black coal. These tutus were supposed to stick out like thorns, exposing the silhouette, making the waist look like the neck of an hourglass, and with every turn, they would cast glints like a mirror ball in a dirty cabaret. His drapes resembled either tofu, a whirlpool, or a wound pulled together with threads. And his dresses, which he called "curtains after a fire," were born like this: he would take old velvet the color of dried blood and literally set fire to its tips so that the pile melted and writhed, leaving charred holes along the hem. He would then soak the fabric in tea and coffee to give it the shade of a rotten rose with stains, like the ceilings in an abandoned theater. The draping in these dresses fell asymmetrically—one side could stretch to the floor with a shaggy fringe, the other would be pulled up like a torn piece of a curtain. When the model walked the runway, these scraps rustled and fluttered, as if in the wind among burnt walls. For Galliano, fabric was not passive: he loved for the material to live its own life, to resist. If silk was too smooth—he crumpled it in the dirt to knock off the shine. If taffeta rustled too loudly—he cut the fibers to make the sound muffled and hoarse, like the sigh of a dying diva. He chose every color with a diabolical intent: copper, like the oxide of old chandeliers; gray-green, like mold on the walls of an opera house; dark plum, like clotted blood in theatrical makeup. In his collection sketches, notes appeared: "Make the fabric look like an old bedspread from Madame de Pompadour's bedroom" or "Add the smell of dust to every fold so the dress smells of oblivion." He didn't just create things—he wanted clothes to become an archive of emotions: fear, desire, betrayal. It was during this period that he began to understand: beauty is not perfection, but shock. He didn't dream of a woman in his dress looking cute, he wanted her to look as if she had just won a duel. Every fold, every cut line was a challenge to boredom. His mannequins stood on the runway not as models but as actresses on the scaffold—their clothes didn't just adorn, they screamed.When John Galliano became the creative director of Dior in 1996, he didn't arrive—he broke in like a hurricane with the smell of powder and wind from a junkyard of old decorations. Dior at the time was a respectable house with archives smelling of dry flowers and memories of the post-war New Look, but Galliano turned this heritage into a backdrop for an opera without rules. Every one of his shows was like a masquerade ball on the ruins of an empire. In the spring-summer 1998 collection, he gathered models who looked like decadent sirens with eyes outlined with black eyeliner an inch thick and lips the color of clotted blood. Their hair lay in greasy waves, like women who had slept the night on a train from Shanghai to Berlin. The clothes were wrapped in layers of taffeta the color of yellow tobacco, crimson wine, dirty pearl; corsets were pulled so tight that the models' backs resembled a cathedral arch. In Dior Haute Couture autumn-winter 2000, Galliano staged a performance where models appeared in crowns of copper thorns, like saints from the iconostasis of hell. Their dresses shone like a dragon's scales: embroideries of millions of glass beads, hand-stitched, caught every light on the runway and reflected it with a thousand microscopic glints, so that the hall resembled a mosaic pattern of a medieval palace. He loved to turn the runway into a moving painting: models walked like actresses from Eisenstein's films, with anguish, with contorted poses, as if every movement was cut from the air with a knife. In the spring-summer 2004 show, women came out in kimonos that, when viewed from the front, looked like monumental constructions, and from the back, they scattered into silk petals, cut from strips of fabric the color of a fading rose, graphite snow, a lunar eclipse. As they moved, the fabric rustled as if someone was slowly tearing the pages of an ancient book. He paid special attention to hats: his favorite milliner Stephen Jones created constructions that were larger than the models' heads—multi-meter spirals resembling spiral staircases, or felt discs from which ribbons dangled like tongues of flame. These hats always created the feeling that a woman could fly away with them at any moment—not from this world, but into her own crazy kingdom. On one of Galliano's signature shows, models walked down a runway laid with mirrored tiles in dresses that looked like old circus posters: striped corsets the color of black coal and dirty gold, skirts with ruffles like can-can dancers, but instead of fun—faces full of arrogance and indifference, like empresses who are tired of ruling. His love for theater was expressed not only in the clothes but also in the atmosphere: at his shows, he filled the hall with the smell of incense, released smoke with the smell of hot iron so that the audience felt as if they were in a cathedral or on a battlefield. The music was always a mix: the ringing of bells, the screech of violins, and then suddenly—electronics with a ragged beat. It was an attack on the senses, a real obsession. In his Dior, you could see precious fabrics that Galliano treated as if he wanted to destroy their perfection: he cut the edges, made burns, tore seams to give them the look of survivors of a fire. The velvet was the color of clotted blood, the satin was the color of chalk on a judge's board, and the lace was the color of ash. No designer has done more to show fashion as both a weapon and a spectacle: in Galliano's shows for Dior, women didn't just walk the runway, they dominated, shocked, seduced. In their eyes, you could read: "You want me, but you are not worthy." Each dress was not an item of clothing but a theatrical prop that turned them into witches, queens, courtesans, pirates.Galliano always knew how to make people at his shows speechless. When he staged Dior shows at the Grand Palais, women in the front rows forgot how to breathe: they clutched their pearl necklaces, their lips parted when a model came out in a dress with a skirt of golden tulle that shimmered like dust on gladiator armor. Men in classic suits exchanged glances because they felt that this was not just a show, but an attack on their idea of decency. The looks in the hall burned like candles at the funeral of the old order. But how could a man who started every morning with ecstasy not burn out? By 2010, John was not just a designer—he was a rock star of fashion. Each show demanded more and more emotion from him, more and more performance. And the evenings became longer and longer: alcohol, substances, sleepless nights in the studio, when he tore up patterns with cries of "This is too boring!", threw away fabric and started all over again. In February 2011, he went into the La Perle cafe in Paris. Tired, on the verge of a nervous breakdown, he began to shout, as witnesses say, anti-Semitic insults. Someone filmed it on a phone. This video went viral faster than his best collections: within a day, it had circled the globe. Dior, which at the time had an absolute intolerance for any racist statements, fired him almost immediately. For the industry that had deified him yesterday, he became a leper. You should have seen the faces of people at the shows in those days: glossy magazine editors walked the Dior catwalks with lost eyes, as if someone had torn out their heart. Rumors about what would happen next hung in the air like smoke at his shows: who would replace him? Could anyone make Dior not just beautiful again, but as exciting as a thriller? Many cried in the dressing rooms: for the Dior team, it was the end of an era. Galliano disappeared. For several years, he did not appear in public, underwent treatment, paid his debts, tried to get his life back on track. In fashion, his name became like an incantation: you say it—and everyone is shaken by a mixture of delight and shame. In 2014, he suddenly returned, and not just anywhere, but to Maison Margiela—a brand where the philosophy of anonymity and deconstruction always reigned. Galliano became a puppeteer again, but with a different temperament: in Margiela, he found a new side. He began to assemble couture looks as if he were sculpting them from the ashes of his old self. The dresses looked like puzzles of fabrics torn to shreds, the colors were like dust on stained glass: pale turquoise, gray with a pink undertone, bronze that looked like green moss on a statue. At one show, models came out in capes of mesh with pieces of vinyl, like glass after an explosion, their faces smeared white, like the masks of spirits from Japanese theater. The audience sighed as in a church when the organ sounds. Someone whispered: "He's back." The music there was also mesmerizing: electronics with a crunch, as if someone was breaking ice, superimposed on the looped sounds of footsteps in an empty corridor. It wasn't music—it was a nightmare in a dream that was impossible not to watch to the end. But in May 2024, it became known that John Galliano was officially leaving Maison Margiela. The news passed like an earthquake through the fashion industry: everyone understood that he had gone back into the shadows, leaving behind emptiness and a tremor. The name Galliano is still spoken in a whisper—like the name of a spirit who knows how to turn fabric into phantasmagoria and shows into a theatrical orgasm. But the return of this ghost to Dior is impossible in a reality where money is more important than madness. In the LVMH offices, they prefer smooth, predictable collections that don't make the audience blush or clench their glasses from too sharp a beauty. Today's Dior is building polished palaces where no ruffle will explode in flame and no hat will be covered in the rust of history. After his exile, everything changed: couture houses began to tiptoe, fashion stopped hissing and growling, as if it had been trained not to bite. The catwalks were cleared of the smell of tobacco smoke and fear, the fabric stopped rustling with threat, and the models stopped looking like demons in silk. Shows turned into polished presentations, where every drape is measured like a lawyer's cold gaze. Instead of dresses that look like living shards of dreams, they now sew neat capsules for impeccable women who don't want to risk even their facial expression. Luxury has become like a museum where it's inappropriate to laugh loudly, and anguish and pain have been replaced by endless beige tranquility.

#Strategic Fragments

Bottega Veneta — Anonymity as the New Luxury

#Women’s Gaze

Female Gravity. Lawrence in Dior.

#Brand Analysis

ROCHAS — A legend moving in harmony with the female silhouette

Paris, 1925. The runways have yet to learn the word “avant-garde,” but women are already beginning to move differently. They shed corsets not out of rebellion, but for the sake of breath. At this moment, at the intersection of fashion and refined bourgeois audacity, the name Marcel Rochas emerges — not a tailor, but more a composer of lines, a conductor of curves. At twenty-two, he opens Maison Rochas to create dresses not for shop windows, but for women who walk, breathe, and live their days with movement in their fabrics. He senses immediately: women’s fashion is not theater. It is the home, the street, the automobile, the dinner table. Rochas brings coats into couture wardrobes, designs dresses with pockets — unthinkable at the time — and unites aesthetics with utility without betraying sensuality. He does not sketch the idealized woman — he sews her life. But the legend lies not in the fabrics. It lies in how Rochas could capture time before it became fashion. By 1934 he is dressing actresses and society muses, but in the 1940s his style becomes a code for a new elegance — one that recalled Dior, yet resonated more intimately. His silhouette was not an architectural manifesto, but a muted breath. In 1945, against the backdrop of post-war Europe, Rochas launches Femme, still called one of the greatest fragrances of the 20th century. Its formula, by master perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, would go on to shape entire eras. Femme smelled of peach, oakmoss, and leather — not as a metaphor for the body, but as a nakedness of memory. The fragrance inhabited the woman not as an icon, but as a personal story. Marcel Rochas becomes one of the first designers to understand the power of perfume as the extension of a dress. He works on packaging graphics, the visual identity of the bottle, creating — long before branding existed — his own code: Rochas is when silk smells like skin. In 1955, at only forty-nine, Marcel dies. His wife, Hélène Rochas, takes the helm, preserving the tone — not expanding, not breaking, but prolonging the breath. She opens the Rochas fashion school, yet the house slowly recedes into the background. Designers change, but none leave a foundational mark. Unlike Chanel, where Karl became a second myth, or Dior, where each step lands with thunder, Rochas lives in a whisper. Its elegance proves too restrained for the 1980s and 1990s. Then, in 2002, Rochas unexpectedly rises again. It is resurrected by Olivier Theyskens — a young Belgian already known for his theatrical subtlety. He does for Rochas what Sarah Burton would later do for McQueen: he returns a soul to fashion. His collections from 2002 to 2006 are haute couture without the need for spectacle. Velvet with misty wool, floral dresses like watercolor, silhouettes in which a woman seemed the heroine of a novel. He was a genius of quiet intensity — and it was in this form that Rochas spoke again. But — finances. Procter & Gamble, owner of the brand, shutters its fashion arm, focusing on perfumes. In 2006, Rochas leaves the runway once more. The house vanishes again. After Theyskens’ departure in 2006, Rochas fades from the catwalk like scent from skin — not instantly, but in stages, leaving behind layers of memory. Only the fragrance line remains, and in the hands of Procter & Gamble the brand exists as a trail without a body. Femme, Alchimie, Lumière — perfumes from different eras that seemed to open abandoned attics of feminine memory. But fashion remains silent. In 2010, the label is acquired by Interparfums — the French perfume giant known for contracts with Lanvin and Montblanc. Interparfums decides to return Rochas to fashion: the body must match the spirit. A slow revival begins. In 2013, Marco Zanini, known for his work at Gianfranco Ferré, becomes creative director. He breathes a new European melancholy into Rochas: volumes recalling Balenciaga in the Cristóbal years, patterns like 1940s porcelain, fabrics that did not shine but seemed to listen. Zanini creates a living archive of sensuality, but departs in 2014. He is succeeded by Alessandro Dell’Acqua, founder of No. 21, ushering in an Italian chapter. His Rochas is more contemporary, ironic, corporeal. Pussy-bow blouses, lurex tights, deliberately girlish ballet flats as if from a 1960s keepsake box. He remains until 2020 — until the pandemic arrives, and fashion once again seeks a voice from the street, not the balcony. Today, in 2025, the house of Rochas stands in a state of restrained reboot. Its creative director is Charlotte Lafayette, a young Frenchwoman from Lanvin, who presented her first capsule collection in autumn 2024. Her Rochas is like silence from which any sound can be shaped. This is not yet a rebirth, but already a pulse. The pieces appear not on runways, but in lookbooks sent to a chosen press. Rochas once again chooses silence as its language. Fragrance is its parallel life. Femme, as a cult, lives on in reissues. In recent years Rochas has released Mademoiselle Rochas, Byzance, Girl. The last became almost viral on TikTok, positioned as a “clean” perfume without parabens, aligned with the neuro-aesthetics of Gen Z. It is a game in new eco-mindedness, yet in the glass bottle one still hears Roudnitska’s echo: peach and oakmoss as a genetic code. At fashion weeks, Rochas is absent. No runway shows. No Vogue Runway flashes. In online stores — rare pieces that often disappear faster than they arrive. This is a brand choosing to exist like a mark on satin, not a flag. Its luxury lies in distance. Its signature — silent desire. Today Rochas is not a moment, but a feeling from another time, returning to you when you pull from a drawer an old silk scarf scented with someone’s neck. And yet it lives. It holds on thanks to aesthetes, collectors, archives — and above all, to those who can hear it even in silence. Perhaps Rochas will never be a brand with millions of Instagram Reels views. But it will always be a brand for those who can discern the scent of time.

#Women’s Gaze

My Prada: Boldness in details and generosity in the soul

#Fashion Notes

Dior Haute Couture SS25: snow-white sleeves as a return to angelic innocence

#Brand Diary

Miu Miu Through the Eyes of the Strategy Director

Alessandro Michele: Fashion as a Palimpsest of the Spirit

#Fashion Insights

McQueen’s Skull: How the Symbol of Death Became a Marker of Boldness and Freedom

#Brand Analysis

Tom Ford: The Director of Desire Who Dressed an Era and Captured It on Film

#Fashion Insights

Chanel Powder Pink: How the Most Girlish Shade Became a Synonym for Grown-Up Confidence

#Aesthetics of Observation

Aroma of Hermès Leather: a scent that can’t be bought

«Deep in every heart slumbers a dream, and the couturier knows it: every woman is a princess.»

#Cultural Analysis

Chanel and the Roaring Twenties: How the Spirit of Jazz and Freedom Forever Changed Fashion

#Brand Analysis

There was no pose in her movement: she walked with her shoulders slightly lowered, like someone who had just released a thousand butterflies and could still hear the rustle of their wings.

#Brand Analysis

Jonathan Anderson: How a Boy from Magherafelt Solved Fashion’s Rubik’s Cube

#Strategic Fragments

Because Dior was born as a dream of femininity.

It began with silence. After a decade of Maria Grazia, Dior resembled a luxurious archive: couture, lace, ruffles, poems about femininity, and all of it was beautiful, like a late velvet evening in a Roman palace. But time is the most ruthless editor, and even the most beautiful stanzas start to sound repetitive. Then Bernard Arnault, a man who can see ten years into the future, lifted his gaze from his reports with a look that was more like an x-ray of the industry, and he understood: Dior needed an architect of mood. Someone who isn't afraid of the silence between notes. And he chose Jonathan Anderson. Anderson is like a sky with a thousand shades at once, and not one of them is repeated. His collections for Loewe were like dreams filmed by a Japanese director with British humor: here is a shirt with a collar that resembles an orchid flower; here is a Puzzle bag that looks like a patchwork map from a game where every detail can disappear and return. He cuts the fabric of the world and reassembles it so that it seems we have never seen a coat before, even though coats have existed for centuries. At Dior, it was clear from the start: this was not a quiet transition. This was antagonism. When he first entered the atelier on Avenue Montaigne, they say he ran his hand over the fabrics in the archive like a pianist over the keys before a concert. He lingered on the gray velvet, the taffeta the color of a faded rose, the buttons with the house's crest—and said that Dior must be both like morning frost and like a night flame. Because the new pop-idea of Dior is about any woman being able to walk into a room and her step sounding like an announcement of her own power. Why did Arnault entrust Anderson with both men's and women's? Because he understood: the world is no longer divided into "for him" and "for her." The world is now a continuum, where a jacket can be armor for both a woman and a man; where a wrap dress speaks not of weakness, but of the right to be unpredictable. Anderson knows how to design such things: at Loewe, he played with proportions like a chef with salt, adding a little more than necessary so that the flavor would be remembered forever. And that decided everything. Arnault wanted not just a designer—he wanted a conductor who could play on both the men's and women's keys. They met in London, in a restaurant where candles stood on the tables, and each one trembled like the hearts of those who knew that the fashion world was about to change. They say they discussed more than just fashion: they talked about how at Loewe he had created a collection of neon threads that glittered under ultraviolet light; about how models at the Loewe show walked in shoes that looked like bears, and about how the audience first laughed, then gave a standing ovation. They also talked about Dior Homme, which was needed like a breath of nitrogen—sharp, but life-saving. In those moments, Anderson understood that he was not just facing a new job—but a chance to reboot the very code matrix of Dior. Because Dior, which was born as a dream of femininity, today must become a manifesto for everyone who no longer wants to choose between elegance and audacity. His goal is to create dresses that will sound like a protest, and jackets that will be silent, but in that silence, say more than any words. Look at the details: in his very first men's collection for Dior, shown in a garden with the geometry of a palace, there were the finest scarves that wrapped around the neck so that they seemed like a second breath; jackets with shoulders like Rodin's sculptures, and boots in which every step sounded like a gunshot. And the audience froze not from beauty, but from the thought: this is dangerously beautiful. He brings a new vision to Dior—he brings the ambivalence that the world loved in Loewe: when a fabric can be tough as armor and soft as a cloud; when a dress can both protect and undress at the same time. And Arnault understood this: he didn't need a designer with a trend, but a philosopher who knows how to sew parables from organza. Now Dior is preparing for Anderson's first women's collection—and the world is holding its breath. Because everyone understands, it will be a question of whether the industry is ready for Dior to stop being a hall of fame and become an arena for courage. Because Anderson has never played by the rules: he loved to invent his own. And now he will write them on the fabric of Dior. They say he already spends hours in the archive on Avenue Montaigne, studying Christian Dior's own patterns. But his gaze is not sentimental—he looks at the past as a map on which you can't drive backwards. And if today you see a Dior dress that looks like a mixture of architecture and abstraction, know this: it's Anderson saying that the new pop-idea of Dior is not about approval, but about the right to your own rules. Because for Anderson, clothing is a statement. It is the alphabet on which we learn to speak about ourselves. And Dior with him is a Dior that will once again be the first word in the language of courage.

#aesthetic observations

Chanel’s milky tweed — a symbol of silent power

There’s a shade in Chanel’s milky tweed that no Pantone chart can pin down: it sits somewhere between a gray Paris morning, before the fog has settled on the balcony grilles, and the cream that slips over a cup’s rim at breakfast in a room at the Ritz. This color neither shouts nor promises; it holds in the pause between inhale and exhale, where every microscopic fiber absorbs silence, as if the cloth could hear your thoughts before you decide to speak them. Milky tweed dislikes direct light: it reveals itself only in half-tones, when a lampshade casts a yellow glow and every fold becomes a raised map of mood. In that relief you can make out stories of those who sat in a corner of the Hemingway Bar and ordered a dry martini at the exact moment a lover’s driver was already waiting across Place Vendôme. This tweed breathes slowly and sounds muffled—like the upholstery of an old sofa that keeps warm traces of long conversations that never quite became confessions. Press your face to Chanel’s milky tweed and you’ll catch the scent of old face powder with a hint of faded roses, warm metal from vintage jewelry clasps, and a faint tobacco trail hidden deep in the seams. You can’t call this scent gentle—it’s more like a secret pact: that you’ll never admit aloud you’ve wanted this jacket since you first saw archive images of Coco on the atelier staircase. In motion, this tweed doesn’t hold like armor: it creases, buckles, shows its weaknesses, and that is precisely its power—like a cut on a perfect leg that draws the eye more than a flawless sheen. Chanel’s milky tweed isn’t out to assert freedom—it knows you pay for it with other things: sleepless nights, the exact skill of falling silent at the right moment, a ring with a cold stone you never wear to work. This tweed doesn’t shout about rights; it is so beautifully quiet that any sentence feels excessive. When I looked at milky tweed in the hall of Villa Paloma, it seemed to me that if silence had a color, it would be this one—soft, dense, like dawn light, and heavy, like the glance once thrown after you that you remember for years.

#Fashion Insights

XXL bags: the soft armor of an age of anxieties and the architecture of silence in the details of Bottega, Gucci, Loewe, Celine, Prada, Dior, and Louis Vuitton

#observational aesthetics — staging luxury: Prada sets the table

#Aesthetics of Observation

The Mirror and the Seam

#fashion notes

Valentino pre-fall 2025: column dresses in a ruby hue and fashion dramaturgy

Paper Kimono: Bain & Company reads to the sound of a Chanel printer

#Дневник бренда

Yves Saint Laurent

Я родился в алжирском свете, где даже тени золотые, и вырос в парижской серости, где каждое пальто звучало, как аккорд. Моё имя шептали, когда кто-то хотел почувствовать себя выше, опаснее, желаннее. В моей мастерской на Rue de Babylone шёлк и бархат спорили, кто из них красивее звучит в тишине. Я не придумывал моду — я настраивал мир, как рояль, чтобы каждая женщина могла сыграть на нём свою симфонию. Я оставался самим собой даже тогда, когда все ждали театра: я дал женщинам сафари-жакеты, чтобы они могли исследовать джунгли города, и прозрачные блузы, чтобы в каждом движении читалась свобода, которой нельзя купить. Я собрал свет Марокко в ткани своих коллекций, чтобы пустынный ветер жил в подолах моих платьев, а багровый цвет розы на губах моделей был не просто макияжем, а красной карточкой скуке.

Я не хотел быть вечным — я хотел быть вечеринкой, о которой помнят. Я знал, что ночь не бывает слишком долгой, если ты умеешь её носить так же, как Le Smoking. Моё наследие — это не архивы, а тысячи женщин, которые однажды поняли: они не обязаны выбирать между хрупкостью и властью, потому что могут быть обеими сразу. Я — Yves Saint Laurent. Я не мода. Я зеркало, в котором женщина впервые увидела своё право на загадочность, свои тёмные и светлые грани, которые не нужно объяснять никому.

Fashion Notes: Viktor & Rolf: The Theatre of Stitches and Fashion’s Silent Scream

It's hard to say where a Viktor & Rolf collection begins and reality itself ends. When the duo of Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren met at the Arnhem Academy of Art in the early 90s, they immediately agreed: fashion for them would not be a craft, but a means to speak about what others are too awkward to whisper. Their first major show at the Hyères Festival in 1993 resonated as a challenge: they didn't just present clothes—they elevated the runway to the level of a theatrical stage, where a dress could be a question, and a collection, an entire novel.

Viktor & Rolf never intended to create purely commercial collections. They dreamed that each of their works would look like a sculpture on the body, like an anatomy of paradox: a jacket with shoulders curved outward; a dress seemingly folded from shattered mirror shards; a skirt molded from hundreds of ruffles that breathe like an organic substance. And if fashion during Galliano's time at Dior was theatre in the genre of "grand style," Viktor & Rolf's work has always been a theatre of the absurd, where every exaggeration acts as a magnifying glass over the essence of fashion.

In 1999, they released the "Russian Doll" collection, where a single model walked onto the stage and Viktor and Rolf, in front of the audience, layered new dresses onto her, coat after coat, like a matryoshka doll. The room held its breath: it was not a show, but a ritual. This scene articulated their core idea: luxury is not the sum of materials, but the process of transforming a woman into an object that cannot be unlayered without losing its magic.

Color for Viktor & Rolf has never been merely a shade, but noise: white for them rings like a deafening silence in the temple of fashion; black—like the void between chords in a symphony. Their prints resemble an infographic of human emotion: the phrases "NO" and "I'M NOT SHY" became symbols of their audacity, as if the dress were whispering a truth to the world that you dare not pronounce.

The soundtracks to their shows are separate performances: in the "Wearable Art" collection, models walked to sounds reminiscent of the reverberation of footsteps in an abandoned theatre, where every echo returned to the viewer as a question: Why do you need fashion if it doesn't surprise you? In these outfits, which simulated paintings in massive frames, Viktor & Rolf showed that clothing can be not only wearable but also an object of contemporary art displayed on a wall.

Even their fragrances became an extension of their philosophy: Flowerbomb is not merely a sweet gourmand perfume, but an explosion against the dull minimalism of the 2000s, as if they took a bomb and filled its casing with rose petals, aiming to destroy not walls, but conventions.

Their mastery of working with fabrics rivals that of architects: pleats at Viktor & Rolf are not soft waves, but frozen droplets of time. The weight of their layers conveys drama, as if a thunderstorm were raging beneath the runway. Even if a dress appears airy, its construction always refers to the discipline they virtuoso possess: inner corsets, frameworks, invisible weights that allow the fabric not just to lie flat, but to hover in the desired plane.

In 2015, when the duo officially stepped away from ready-to-wear to fully focus on couture, the fashion world sighed with relief and anxiety simultaneously: they were no longer constrained by commercial frameworks, and every new collection began to transform into an independent art expression. In their subsequent works, one can find hints of both Salvador Dalí and Björk: surrealism, anxiety, irony—everything that turns clothing from a functional object into a manifesto.

Today, Viktor & Rolf are once again at the peak of their strange, absurd poetry of fashion. After several years of relative quiet, their Instagram came alive like a doll opening its eyes: they released new couture collections in which models once again seem to be wearing not dresses, but phrases frozen in the air. Their latest shows are a return to their signature theatre: corsets with gigantic bows, dresses that look like they were cut from comic books, and slogans that drift through the room like the echo of rebellious dreams.

Instead of pandering to trends, Viktor & Rolf continue their show-within-a-show: their collections are like dreams understood only by those who are not afraid of their own contradictions. Every appearance of their new work is a reminder that there is a place in fashion for chaos, laughter, and tenderness all at once. And yes, while some build profit, Viktor & Rolf continue to build paradoxes.

#brand analysis

A living archive of brands.

1️⃣ Brand Analysis — Micro-essays, observations on positioning, communication, details of advertising, stores, exhibitions, and packaging.

2️⃣ Quotes on Luxury — Words from great designers, philosophers of luxury, clients; or your own original, aphoristic, and brief thoughts.

3️⃣ Micro-Content — Ultra-short notes (1–3 sentences) with a sharp meaning, ideal for social media and quick insertions on the page.

4️⃣ Strategic Fragments — How a brand solves positioning or identity challenges, and the why behind a specific move or action it takes.

5️⃣ The Feminine Perspective — Personal experience, emotions, subjective perception of the client (yours or an imagined heroine's) from interacting with the brand.

6️⃣ Cultural Analytics — A look at the brand through a socio-cultural prism: what it means for society and what cultural layer it reveals.

7️⃣ Fashion Notes — Fresh mini-reports on collection launches, current accessories, and trends, but all presented as reflection rather than news.

8️⃣ Brand Diary — Stories or sketches told from the brand’s perspective or about how the brand exists across time and space.

9️⃣ Fashion Insights — Unexpected ideas or thoughts about fashion and luxury revealed through small details.

🔟 Aesthetics of Observation — Short texts about gestures, shades, forms, sounds, scents associated with the brand; the details that build the emotional landscape.

CONTENT EXCLUSIONS

* General reflections not related to brands or life in general (e.g., musings on apples or dreams outside the context of luxury and brands).

* Texts not tied to the world of aesthetics, luxury, meaningful constructions, or client experience.

* Random stream of consciousness that does not connect to the page's positioning as "notes in the margins of brands."

WHY THIS IS IMPORTANT

Each of the 26 pages of Elaya.Space is like an independent chapter of a book. The "Marges et Soulignées" page must be dedicated specifically to the intellectual, cultural, and analytical layer of brands, and not drift into the realm of general thought. Otherwise, the pages will become indistinguishable to the reader. A clear agenda allows the visitor to understand: what this page is for, why it is needed, and what makes it unique compared to the others.